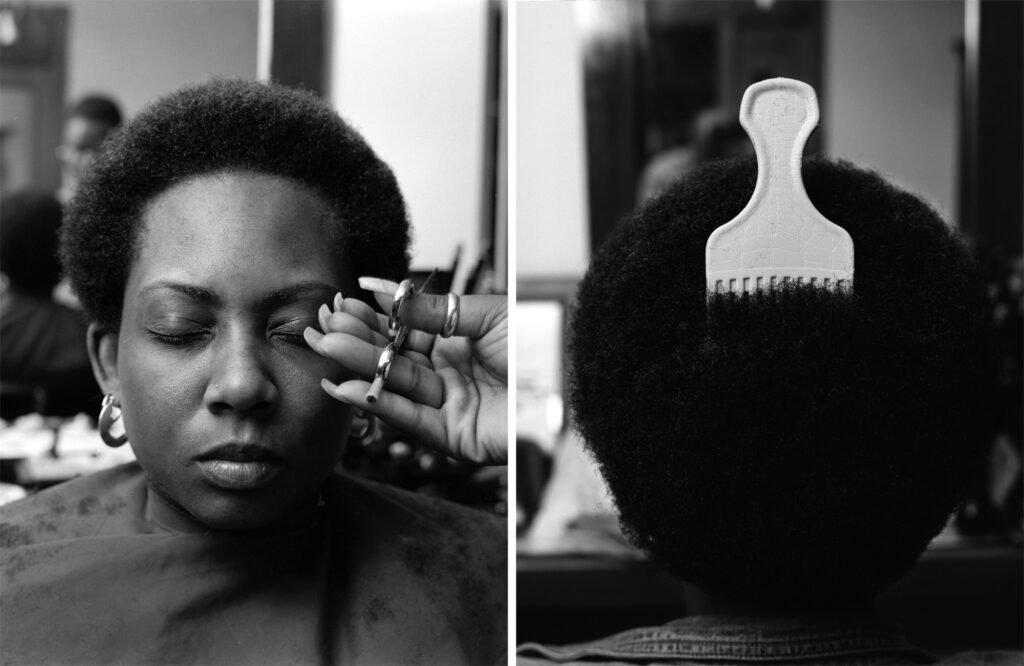

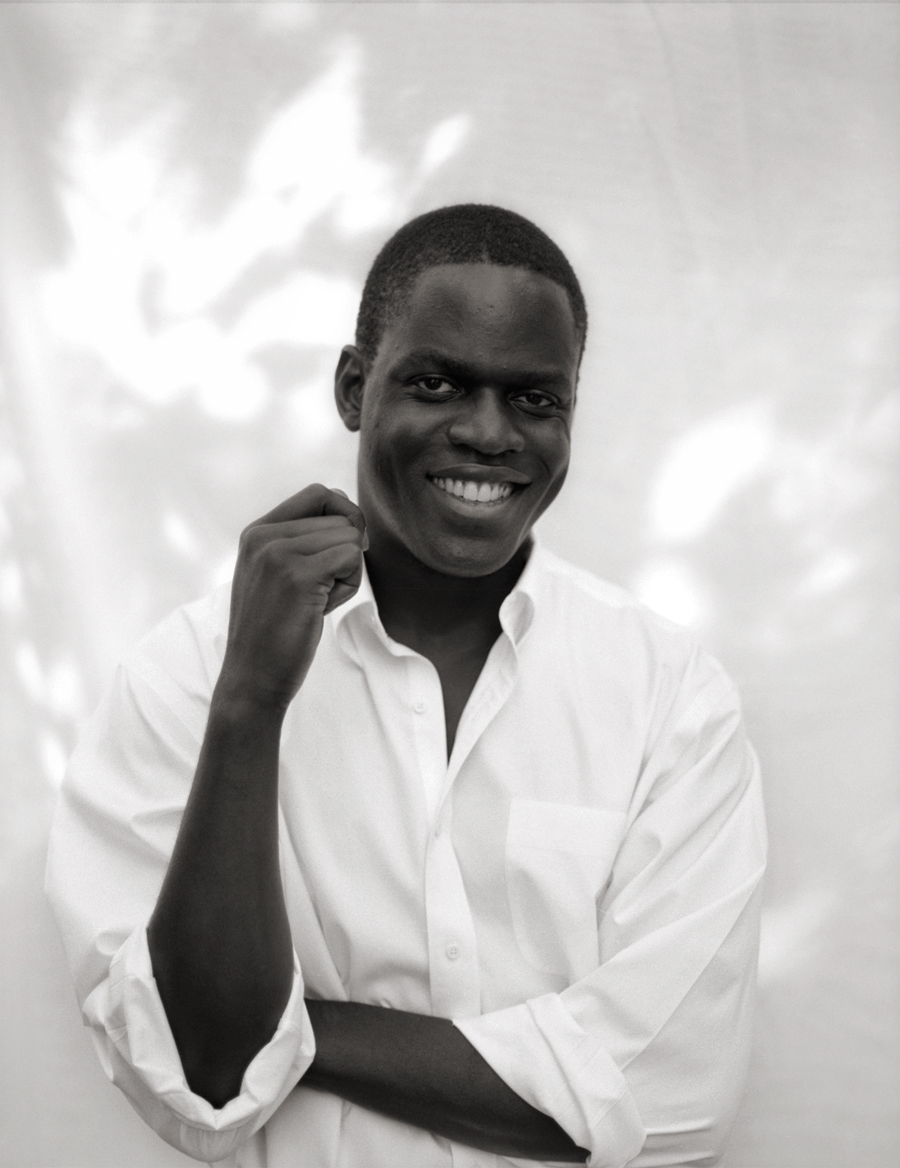

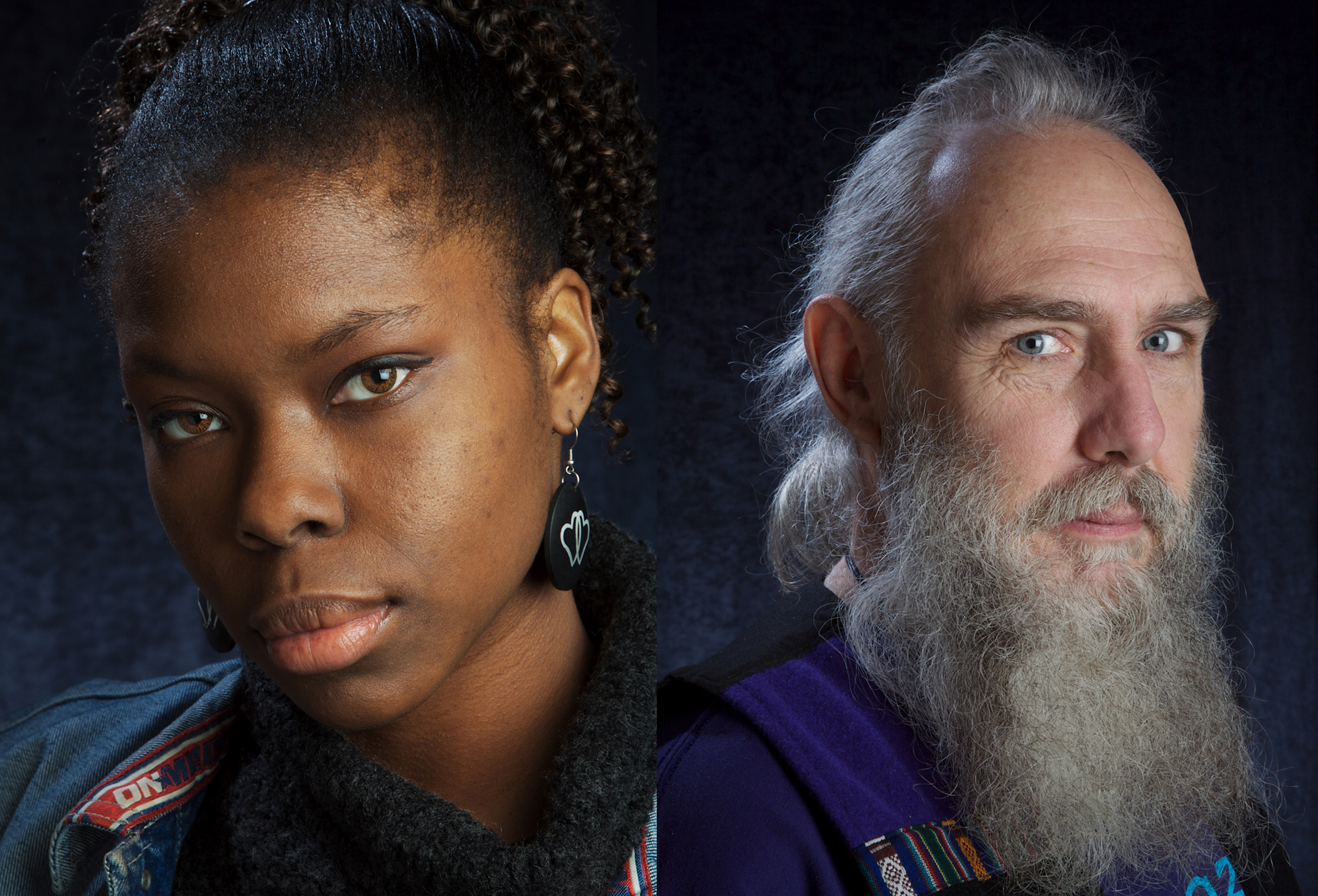

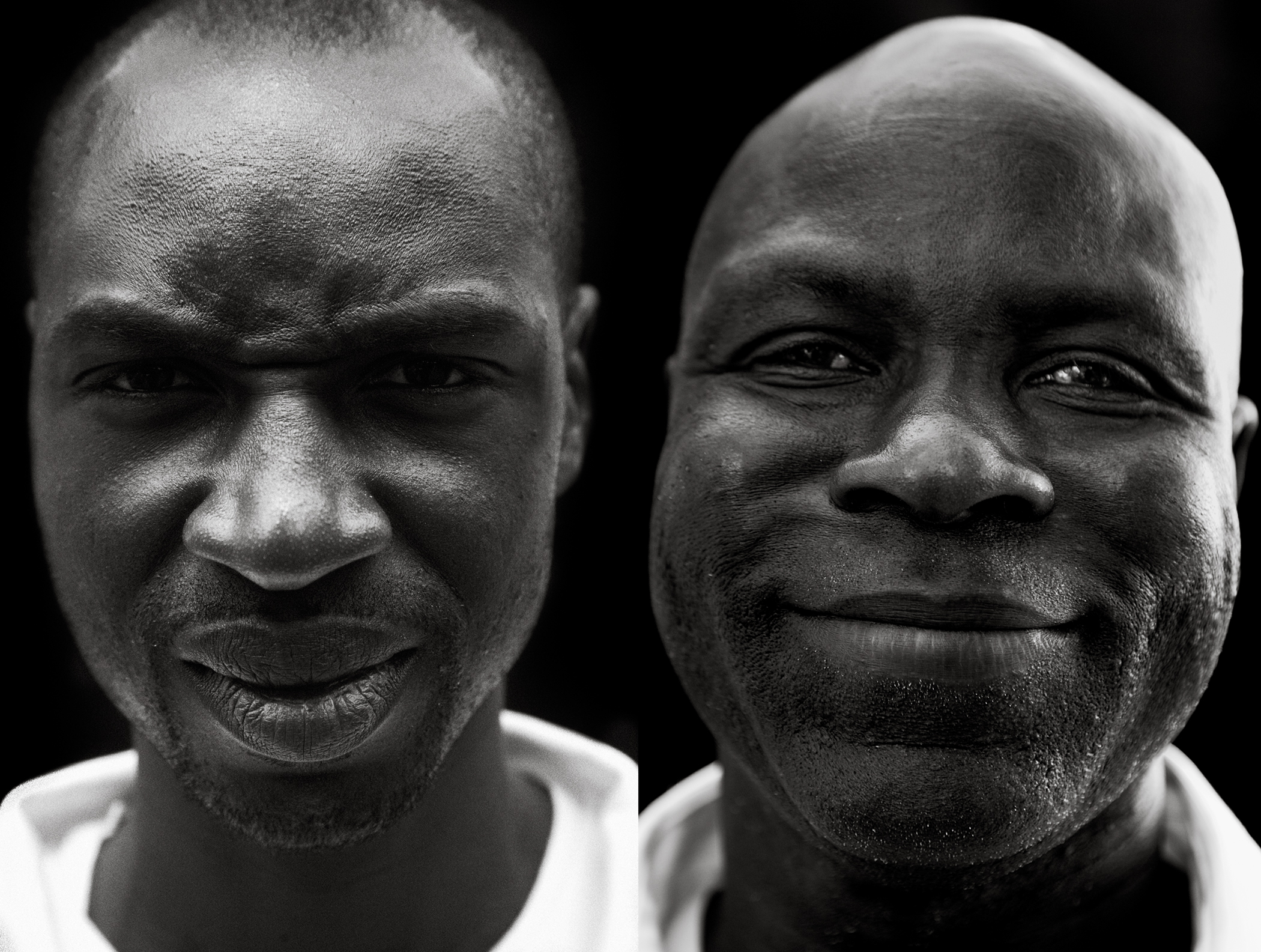

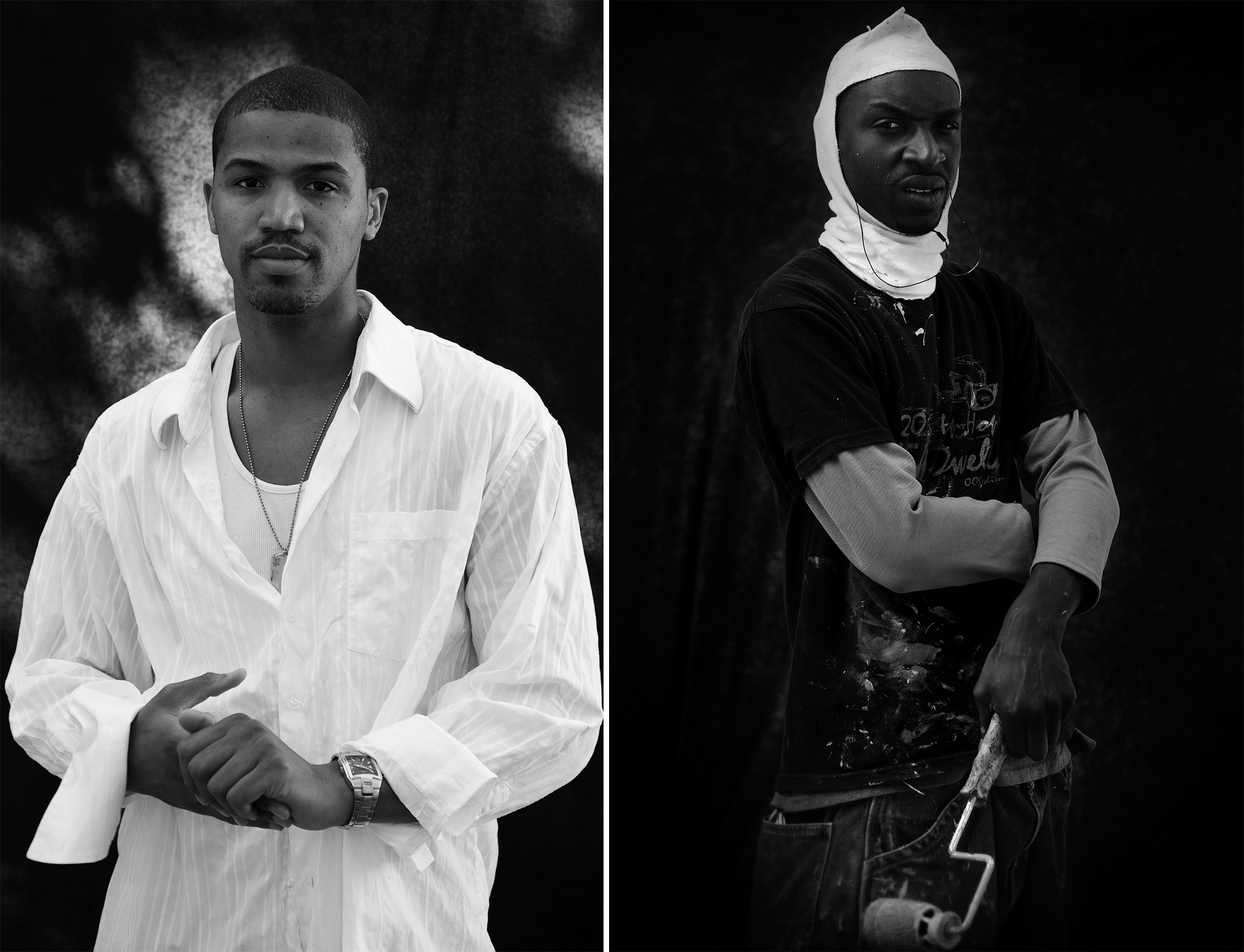

Thoroughfares, Detours & Cul-De-Sacs | Portraits in the 2000s

Evan Flory Barnes | 2007

The images in this gallery forced me to give up photography! Sort of. This incendiary click-baity lead-in, like most headlines, is peppered with a smidge of truth. I’ll explain.

My biggest challenge in my relationship with my photography is finding a voice that feels true and full. A voice that is complicated and comfortable. A way of looking at the world that dives into the things that I am certain about and the things that make me anxious and questioning with equal aplomb. Since I took up photography I have been searching for a certain kind of fearlessness of pursuit. That is how I look at my photography and all of my creative work. It is a chase, a quest, a journey, a mystery that can only be pursued with a certain mastery of the tools, the techniques and the language.

When I was taking English classes at Seattle Central Community College in the late 1980s my professor, JT Stewart, would constantly remind me to practice as many forms and genres in poetry writing as possible. “You must know the rules in order to break them”, she would say before turning my drafts into red abstract drawings. This lesson stuck with me, not so much because it was new, but because it was an essential truth that could not be ignored.

I was already unwittingly applying it to my incubating vocation as a photographer. My bedroom walls were papered with photos torn from magazines, on post and greeting cards, pulled from album covers and saved from newspapers. I meditated on these images, studying the light, shadows and forms. I wanted to know how they worked, how they were made and felt like all the answers to my questions were in the images themselves. This was a pastime I had been engaged in since I was a sophomore in high school. Unlike poetry and writing in general, it would be another five years before I would actually have the means to start my study of visual linguistics.

In 1993 I bought my first camera kit, a used Canon AE-1 body with accompanying 50mm, 35mm and 70-210mm lenses, as a financially strapped college student. It would be years before I could afford body and lens upgrades. Even longer before I could get real studio lighting and other tools. In those early years I improvised, purchasing used flashes and modifying them with aluminum, plain paper and black painted cardboard modifiers, all cobbled together by the sturdiest tape I could afford. By 1998 I purchased my first used studio lighting kit, a Novatron 400 with two light heads and an assortment of modifiers. It was a beast of a kit, big and heavy. Nevertheless I was ecstatic to have something, anything to push forward with. At every stage of equipment fabrication or acquisition I tried to push the limits of what I could experiment with and learn about lighting and composition. It became a bit of an obsession, mainly because it felt like my biggest bottleneck between where I was and where I wanted to be as a photographer. After spending so many years studying the visual language of photography, I was literally bursting with ideas about what I might do. Still, I had to put in real practiced work to learn and master the technicalities. Then I had to figure out how to apply those skills in service of my voice. It was a long road. I constantly felt like I was trying to catch up with myself. As much as I loved it, the process of learning and practicing was damn frustrating when I could barely afford the tools to exercise all of the ideas swimming around in my head.

Snow Seck | 2008

I share all of this backstory because the anticipation, frustration, anxiety, excitement and experimentation that defined my first eight years as a photographer, continued to plague me in new and unexpected ways. I acquired the equipment I desired, practiced with it, grew in my mastery, and began to experiment with different things. I was shooting for ColorsNW Magazine and other publications, carrying a roster of editorial assignments monthly. I was working with other

journalists, editors and publishers to deliver clean images on tight, repeating deadlines. The rigor sharpened, or maybe narrowed, my style.

I realized by the mid 2000s that my hard push to master various technical forms in photography had left me dissimilarly unbalanced than my earlier years. I had gotten to a place of comfort with my equipment and various forms of photographic execution. I was working much more regularly on assignments. As my confidence in this area grew, my emotional connection to my own imagery began to flatten. I was unsure about how to apply all that I learned to what I wanted to say personally.

Some of these blocks were existential. I needed to make money with my photography. I worked gigs, delivering a product, editorial or commercial, for a long string of clients. I struggled on a freelancer’s income to support a family in a city that was getting more expensive to live in by the day.

Harrison High Gloss | 2011

I was still shooting personal work somewhat regularly. The results felt shallow and stilted. Portraiture was a main focus, not necessarily by choice. Family life didn’t allow the time nor money to go out and just wander with my camera, or travel at the drop of the hat to photograph something that might catch my interest. Portraiture fit neatly alongside all of my other responsibilities in life. I found myself creating in an increasingly narrow band. I don’t disparage the work I created

during that time. In every objective way the work was good, proficient, well-executed. However, itdidn’t have the lyricism that I felt so much of my early experimentation promised. I needed the uncertainty, spontaneity and complexity of my early work. Without a sense of how to get back to that, my anxiety grew.

By 2010 I decided to take an indefinite hiatus from photography. I needed a break to figure out what I wanted, what I needed, from my personal practice. I needed time away from photography to understand what my future with it could be. As of writing this note it has been thirteen years since I shed my identity as a photographer. During the last decade or so I have taken plenty of photos, but only recreationally. All of my ‘work’ during this period has been low stakes and casual. I am only just now beginning to feel like I might be able to approach it with the possibility of there being love and freedom again.

through the works of Roy DeCarava, Robert Frank, Pierre Verger, and Sabastaio Saldgado. These photographers created stunning bodes of work that were as focused as they were personal. I wanted to find in myself the ability to create bodies of images that excited me in the same way. One-off image love affairs sometimes feel like luck, not the fruits of hard work inside an enduring marriage

‘Thoroughfares, Detours & Cul-De-Sacs’ is dedicated to that crucial period of creative uncertainty. With each image I am retracing the places where the way forward felt open and clear, the places where the terrain was strange and confusing, and the places that felt like I was tracking my own footprints in a circle. I’ll let you guess which images are which.