Two major transitions happened between the fall of 2000 and the summer of 2001. First, I left Atlanta for Seattle in October 2000 after living there for nearly a decade. Moving back home, the timing of it, would be the most significant choices shaping my career, personal life and my art. Over the previous four years I had slowly begun to make a life working on film and tv shoots through the southeastern states, Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee. I held down contract jobs as a corporate audio visual tech while hustling my

wedding and portrait photography on the side. I kept a nice, inexpensive apartment with a roommate, and lived a relatively austere life.I still spent most of my extra income on photography and media equipment and supplies.

Looking back, if I were to describe the energy informing my photographs of those early years I would say they had a kind of urgent curiosity. They feel like I was constantly pushing into the wild, beating back the bush, looking for something I knew was there, but uncertain of what that something was. There are some images, which I have never shown publicly but someday soon may,that are incredible in that I even had the courage to take them. In many ways I had no filter. So often my shooting was a visceral response to a question posed in the exact moment that I released the shutter. I love the untamed, almost feral nature of that gaze. I look back and wonder if it is possible for me to summon up that energy again.

That energy shifted, radically, upon my move back to Seattle.

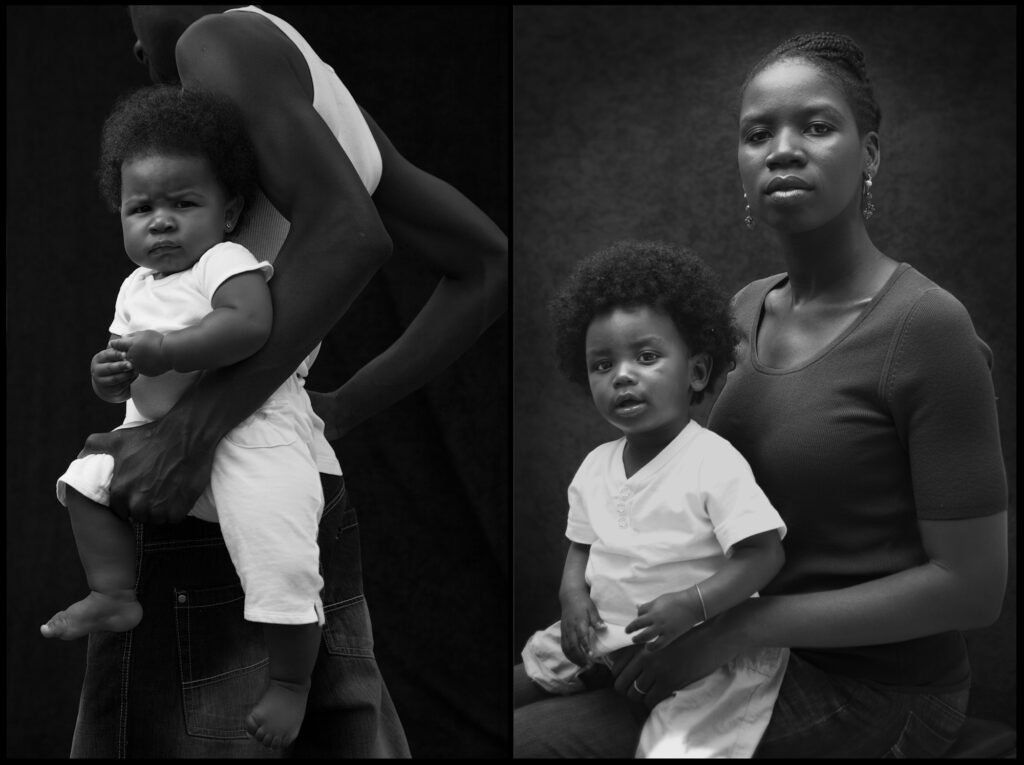

My new circumstances demanded something different from my psyche. My first daughter was born in 1991, the same year I left Seattle to attend college in Atlanta. I spent ten years as a part-part-time father, functionally a childless bachelor in my day-to-day life. Upon return I became the custodial parent and my life settled into a new kind of domestic regularity. On top of this, I was once again fully immersed in the daily life of my immediate and extended family. Seattle’s film industry was sparse to non-existent, at least in the way that I

had become accustomed to. The demands of fatherhood and establishing a new life in an old, familiar place pushed me to lean heavily on my skills as a photographer to make a living.

These tectonic shifts changed my creative consciousness.

For the previous five years I had committed myself to a self-guided study of the photographic industry. Alongside matters of promotional portfolios, rate sheets, freelance job bids, and minimum daily income formulas, there was the question of what kinds of images were saleable. In the same way that I had ingested the aesthetics of mid 20th century street and documentary photographers in my formative years, I took in the work of the era’s most prominent working commercial photographers. Albert Watson, Annie Liebowitz, Rodney Smith, Herb Ritts and many others loomed large. I also had years of photo studio assistant work under my belt. Atlanta had some of the most prolific working black commercial photographers. I assisted some of the best of them. Earnest Washington is a standout example. I had absorbed the aesthetics and technical skills to imagine creating work like these photographers, but hadn’t had the opportunity to test what I thought I learned. Nonetheless, I felt ready to make the shift, if not for practical working experience working my own commercial gigs, then for sheer hubris/confidence in myself. A confidence bolstered by absolute necessity.

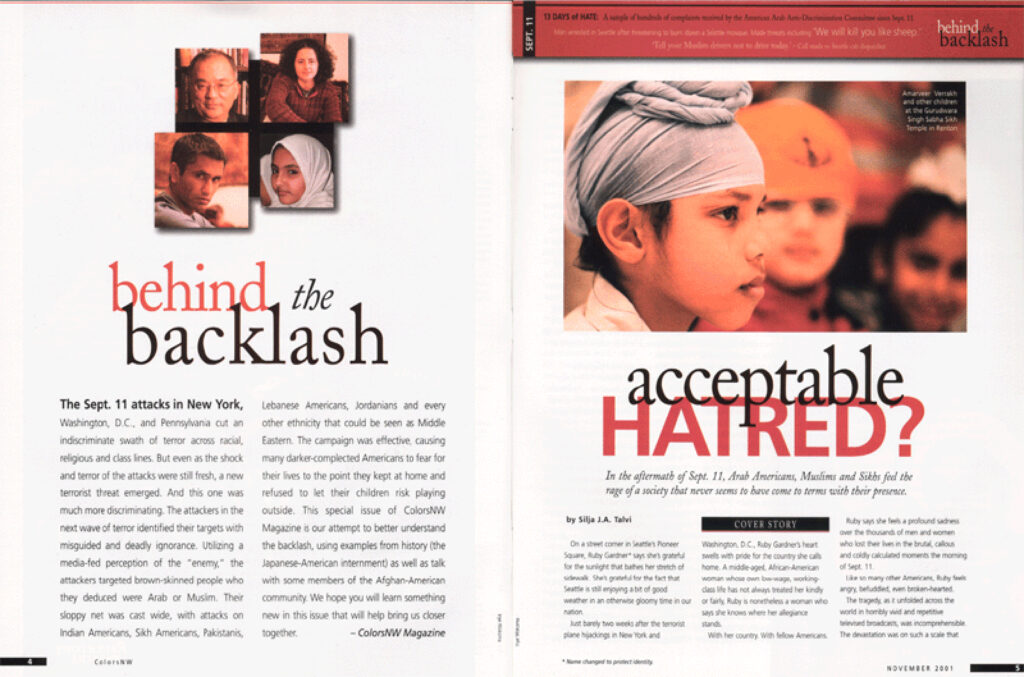

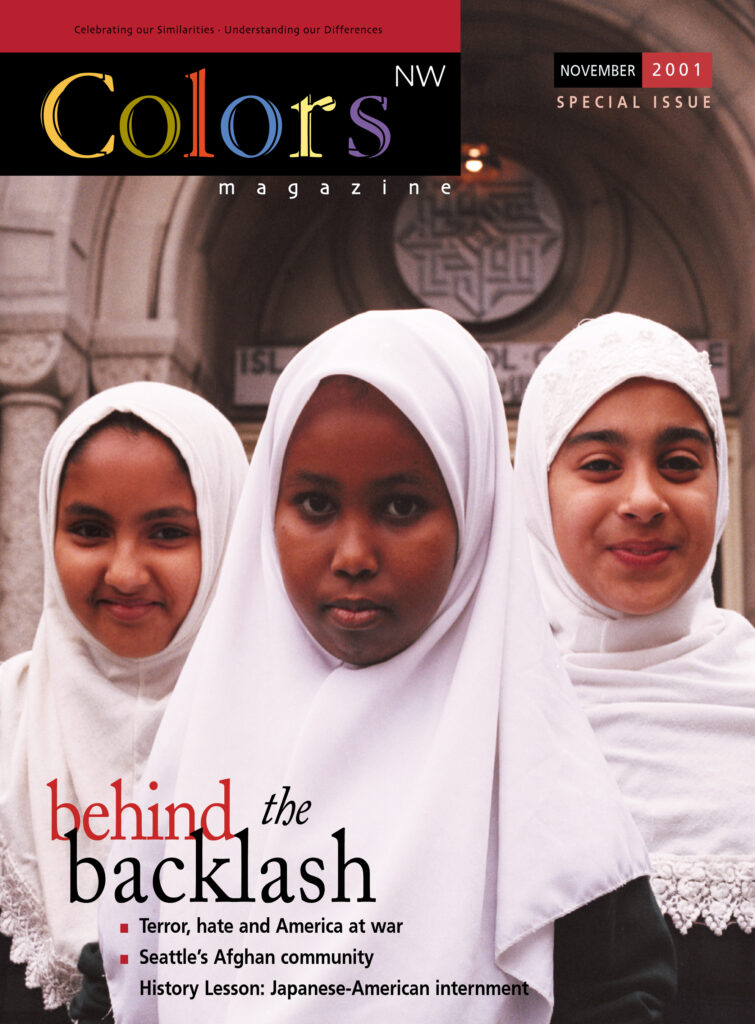

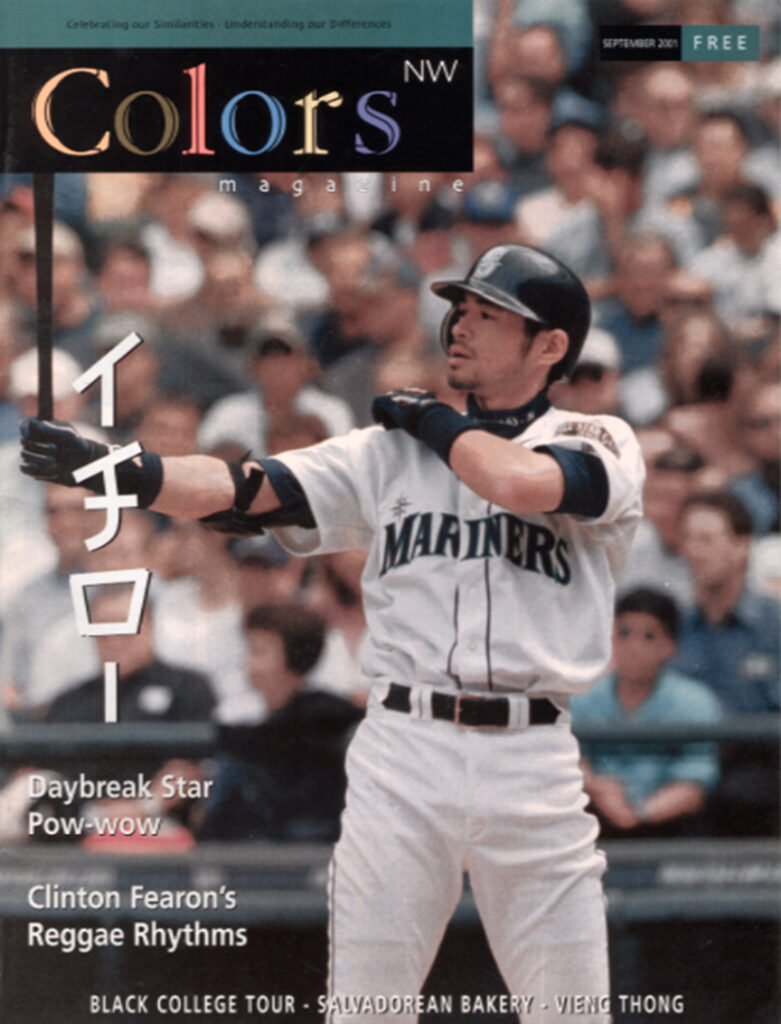

This brings me to the second major change shaping my work. In the summer of 2001 I landed my first regular job as a photographer. I was fortunate enough to be hired as the staff photographer for ColorsNW Magazine, a full color glossy print publication. ColorsNW published stories about communities of color across Washington State. By my third issue shooting for ColorsNW, I was producing feature images

for stories about Muslim Americans in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Suddenly I was on never-ending rolling deadlines. I was shooting under the direction of an editor and publisher. My images had to align with the tone and style of the articles they accompanied. Cover images had to be composed tightly layout and visually arresting enough to stand out on a crowded newsstand. The editor needed to know now, now, now, how assignments were progressing. The publisher needed to know if we had a ‘money shot’ for the cover that would excite advertisers and boost subscriptions. That wild urgency that I defined my personal work up until that time? Yeah, I had to tighten all that up.

This was an era of steel sharpening steel.

Even with the wild roaming nature of my eye during my first eight years shooting. I was sharpening my ability to shoot in the most challenging situations. Poor lighting, uncontrolled subjects and settings, perfect shots that vanish just as quickly as they appear. The question of lighting, composition, subject matter and subject consent. Pushed myself to understand all of these things between 1993 and 2001. In 2001 I would have to deploy everything I learned to create

disciplined, consistently usable, and hopefully inspiredimages on assignment. My editor, Naomi Ishisaka, was a kind and insistent trial by fire. She needed what she needed and was shy about letting me know. But she was alway calm and respectful. LOL. I loved and appreciated all of that about her, even when it was frustrating and anxiety inducing.

Invariably all of this personal and professional change would also transform the fundamentals of my own creative work. The way I pursued photography I created for myself mirrored the demands of my professional endeavors. I began to think more broadly about intent and use. I slowed down and mapped out ideas that I would produce and execute. The digital revolution descended upon the photography world and I embraced and incorporated that as well. There was no loss of that wandering in a creative wilderness, it was the pace and process of the search that changed.

These galleries map as much of this growth and change as I can articulate. They are also a necessary precursor to understanding the work in my Exhibition, Video and Collage galleries as those works are flowering fruits that emerge out of the necessity and immediacy of what I learned in this shift in my photographic practice.